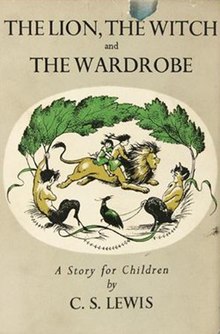

Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe Original Edition Art

Commencement edition dustjacket | |

| Author | C. South. Lewis |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Pauline Baynes |

| Embrace artist | Pauline Baynes |

| State | U.k. |

| Linguistic communication | English |

| Series | The Chronicles of Narnia |

| Genre | Children's fantasy, Christian literature |

| Publisher | Geoffrey Bles |

| Publication date | xvi Oct 1950 |

| Media type | Impress (hardcover and paperback), e-volume |

| OCLC | 7207376 |

| LC Form | PZ8.L48 Li[ane] |

| Followed by | Prince Caspian |

The Panthera leo, the Witch and the Wardrobe is a fantasy novel for children by C. Due south. Lewis, published past Geoffrey Bles in 1950. It is the kickoff published and best known of seven novels in The Chronicles of Narnia (1950–1956). Among all the author's books, it is besides the well-nigh widely held in libraries.[two] Although information technology was originally the first of The Chronicles of Narnia, it is volume ii in recent editions that are sequenced by the stories' chronology. Like the other Chronicles, it was illustrated past Pauline Baynes, and her work has been retained in many later editions.[one] [iii]

Most of the novel is set in Narnia, a state of talking animals and mythical creatures that is ruled past the evil White Witch. In the frame story, iv English children are relocated to a big, old country house following a wartime evacuation. The youngest, Lucy, visits Narnia iii times via the magic of a wardrobe in a spare room. Lucy's three siblings are with her on her third visit to Narnia. In Narnia, the siblings seem fit to fulfill an old prophecy and find themselves adventuring to save Narnia and their own lives. The lion Aslan gives his life to salvage 1 of the children; he afterward rises from the dead, vanquishes the White Witch, and crowns the children Kings and Queens of Narnia.

Lewis wrote the book for (and dedicated it to) his goddaughter, Lucy Barfield. She was the daughter of Owen Barfield, Lewis'southward friend, teacher, adviser and trustee.[four] In 2003, The Panthera leo, the Witch and the Wardrobe was ranked ninth on the BBC's The Large Read poll.[five] Time magazine included the novel in its list of the 100 Best Young-Adult Books of All Time,[6] likewise equally its list of the 100 all-time English-language novels published since 1923.[vii]

Plot [edit]

Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy Pevensie are evacuated from London in 1940, to escape the Blitz, and sent to live with Professor Digory Kirke at a large house in the English language countryside. While exploring the house, Lucy enters a wardrobe and discovers the magical world of Narnia. Here, she meets the faun named Tumnus, whom she addresses every bit "Mr. Tumnus". Tumnus invites her to his cavern for tea and admits that he intended to written report Lucy to the White Witch, the faux ruler of Narnia who has kept the state in perpetual winter, but he repents and guides her back dwelling house. Although Lucy's siblings initially discount her story of Narnia, Edmund follows her into the wardrobe and winds upwardly in a separate surface area of Narnia and meets the White Witch, who calls herself the Queen of Narnia. The Witch plies Edmund with Turkish delight and persuades him to bring his siblings to her with the promise of being made a prince. Edmund reunites with Lucy and they both return home. Notwithstanding, Edmund denies Narnia's existence to Peter and Susan subsequently learning of the White Witch's identity from Lucy.

Presently after, all four children enter Narnia together, but find that Tumnus has been arrested for treason. The children are befriended by Mr. and Mrs. Beaver, who tell them of a prophecy that claims the White Witch's dominion will finish when "ii Sons of Adam and ii Daughters of Eve" sit on the iv thrones of Cair Paravel, and that Narnia'southward true ruler – a great lion named Aslan – is returning at the Stone Table after several years of absence. Edmund slips away to the White Witch's castle, where he finds a courtyard filled with the Witch's enemies turned into stone statues. Edmund reports Aslan's return to the White Witch, who begins her motility toward the Rock Table with Edmund in tow, and orders the execution of Edmund's siblings and the Beavers. Meanwhile, the Beavers realise where Edmund has gone, and pb the children to encounter Aslan at the Rock Table. During the trek, the group notices that the snow is melting, and take it every bit a sign that the White Witch's magic is fading. This is confirmed by a visit from Father Christmas, who had been kept out of Narnia by the Witch'southward magic, and he leaves the group with gifts and weapons.

The children and the Beavers reach the Stone Table and run across Aslan and his regular army. The White Witch's wolf helm Maugrim approaches the camp and attacks Susan, simply is killed past Peter. The White Witch arrives and parleys with Aslan, invoking the "Deep Magic from the Dawn of Time" which gives her the right to kill Edmund for his treason. Aslan then speaks to the Witch solitary, and on his return he announces that the Witch has renounced her merits on Edmund's life. Aslan and his followers then move the encampment on into the nearby forest. That evening, Susan and Lucy secretly follow Aslan to the Rock Table. They sentry from a distance as the Witch puts Aslan to death – every bit they had agreed in their pact to spare Edmund. The next morning, Aslan is resurrected by the "Deeper Magic from earlier the Dawn of Fourth dimension", which has the power to reverse death if a willing victim takes the place of a traitor. Aslan takes the girls to the Witch's castle and revives the Narnians that the Witch had turned to stone. They join the Narnian forces contesting the Witch'south army. The Narnian army prevails, and Aslan kills the Witch. The Pevensie children are and so crowned kings and queens of Narnia at Cair Paravel.

After a long and happy reign, the Pevensies, now adults, go along a hunt for the White Stag who is said to grant the wishes of those who catch it. The four arrive at the lamp-post marking Narnia's entrance and, having forgotten about information technology, unintentionally pass through the wardrobe and return to England; they are children over again, with no time having passed since their deviation. They tell the story to Kirke, who believes them and reassures the children that they will return to Narnia one twenty-four hour period when they least expect it.

Main characters [edit]

- Lucy is the youngest of 4 siblings. In some respects, she is the master character of the story. She is the commencement to discover the land of Narnia, which she enters inadvertently when she steps into a wardrobe while exploring the Professor'due south firm. When Lucy tells her three siblings almost Narnia, they do not believe her: Peter and Susan think she is just playing a game, while Edmund persistently ridicules her. In Narnia, she is crowned Queen Lucy the Valiant.

- Edmund is the second-youngest of four siblings. He has a bad relationship with his brother and sisters. Edmund is known to be a liar, and often harasses Lucy. Lured by the White Witch'south promise of power and an unlimited supply of magical treats, Edmund betrays his siblings. He afterward repents and helps defeat the White Witch. He is eventually crowned Male monarch Edmund the Just.

- Susan is the second-oldest sibling. She does non believe in Narnia until she actually goes there. She and Lucy accompany Aslan on the journey to the Stone Table, where he allows the Witch to have his life in identify of Edmund's. Disposed to Aslan's carcass, she removes a muzzle from him to restore his nobility and oversees a horde of mice who gnaw away his bonds. She then shares the joy of his resurrection and the try to bring reinforcements to a disquisitional battle. Susan is crowned Queen Susan the Gentle.

- Peter is the eldest sibling. He judiciously settles disputes between his younger brother and sisters, often rebuking Edmund for his attitude. Peter likewise disbelieves Lucy's stories almost Narnia until he sees information technology for himself. He is hailed every bit a hero for the slaying of Maugrim and for his command in the battle to overthrow the White Witch. He is crowned High King of Narnia and dubbed King Peter the Magnificent.

- Aslan, a lion, is the rightful King of Narnia and other magic countries. He sacrifices himself to save Edmund, simply is resurrected in time to aid the denizens of Narnia and the Pevensie children confronting the White Witch and her minions. As the "son of the Emperor beyond the ocean" (an innuendo to God the Male parent), Aslan is the all-powerful creator of Narnia. Lewis revealed that he wrote Aslan every bit a portrait, although not an allegorical portrait, of Christ.[8]

- The White Witch is the land's cocky-proclaimed queen and the primary antagonist of the story. Her reign in Narnia has fabricated winter persist for a hundred years with no end in sight. When provoked, she turns creatures to stone with her wand. She fears the fulfillment of a prophecy that "two sons of Adam and two daughters of Eve" (pregnant two male humans and two female humans) will supplant her. She is usually referred to as "the White Witch", or but "the Witch". Her actual proper noun, Jadis, appears in one case in the discover left on Tumnus'south door later his abort. Lewis later wrote a prequel to include her dorsum story and account for her presence in the Narnian world.

- The Professor is a kindly sometime admirer who takes the children in when they are evacuated from London. He is the first to believe that Lucy did indeed visit a land called Narnia. He tries to convince the others logically that she did non make information technology up. After the children return from Narnia, he assures them that they will return one day. The book hints that he knows more of Narnia than he lets on (hints expanded upon in afterward books of the serial).

- Tumnus, a faun, is the beginning individual Lucy (who calls him "Mr. Tumnus") meets in Narnia. Tumnus befriends Lucy, despite the White Witch'due south continuing order to turn in any human he finds. He initially plans to obey the social club but, afterwards getting to similar Lucy, he cannot conduct to alert the Witch's forces. He instead escorts her dorsum towards the condom of her own state. His good deed is later given abroad to the Witch by Edmund. The witch orders Tumnus arrested and turns him to stone, but he is later on restored to life by Aslan.

- Mr. and Mrs. Beaver, two beavers, are friends of Tumnus. They play host to Peter, Susan and Lucy and lead them to Aslan.

Writing [edit]

Lewis described the origin of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe in an essay titled "It All Began with a Motion picture":[9]

- The King of beasts all began with a pic of a Faun carrying an umbrella and parcels in a snowy wood. This movie had been in my mind since I was most xvi. Then i twenty-four hour period, when I was about 40, I said to myself: 'Let's effort to make a story near it.'

Shortly before the Second Globe State of war, many children were evacuated from London to the English countryside to escape bombing attacks on London by Nazi Germany. On 2 September 1939, iii schoolhouse girls, Margaret, Mary, and Katherine,[10] [xi] came to live at The Kilns in Risinghurst, Lewis's abode three mi (4.8 km) east of Oxford city middle. Lewis later suggested that the feel gave him a new appreciation of children, and in late September,[12] he began a children's story on an odd sheet that has survived as part of some other manuscript:

- This volume is about iv children whose names were Ann, Martin, Rose and Peter. Only it is most well-nigh Peter, who was the youngest. They all had to go away from London suddenly because of Air Raids, and because Begetter, who was in the Army, had gone off to the State of war and Mother was doing some kind of war piece of work. They were sent to stay with a kind of relation of Female parent's who was a very onetime professor who lived all past himself in the country.[xiii]

How much more of the story Lewis and so wrote is uncertain. Roger Lancelyn Dark-green thinks that he might even have completed it. In September 1947, Lewis wrote in a alphabetic character about stories for children: "I have tried ane myself, simply information technology was, by the unanimous verdict of my friends, then bad that I destroyed it."[14]

The plot element of entering a new world through the dorsum of a wardrobe had certainly entered Lewis's heed by 1946, when he used it to describe his first run across with really good poetry:

- I did not in the to the lowest degree feel that I was getting in more quantity or improve quality a pleasance I had already known. It was more than every bit if a closet which one had hitherto valued as a identify for hanging coats proved 1 day, when you opened the door, to lead to the garden of the Hesperides ...[xv]

In Baronial 1948, during a visit by an American writer, Chad Walsh, Lewis talked vaguely almost completing a children'south book he had begun "in the tradition of E. Nesbit".[16] Later on this chat, non much happened until the beginning of the next year. So everything changed. In his essay "Information technology All Began With a Picture", Lewis continues: "At first I had very lilliputian idea how the story would go. Just and then suddenly Aslan came bounding into it. I think I had been having a proficient many dreams of lions about that fourth dimension. Autonomously from that, I don't know where the Lion came from or why he came. Just one time he was in that location, he pulled the whole story together, and soon he pulled the six other Narnian stories in later him."[17]

The major ideas of the volume echo lines Lewis had written 14 years earlier in his alliterative poem "The Planets":

- ... Of wrath ended

- And woes mended, of winter passed

- And guilt forgiven, and good fortune

- JOVE is master; and of jocund revel,

- Laughter of ladies. The lion-hearted

- ... are Jove's children.[18]

This resonance is a central component of the instance, promoted chiefly by Oxford University scholar Michael Ward, for the seven Chronicles having been modelled upon the vii classical astrological planets, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe upon Jupiter.[19]

On 10 March 1949, Roger Lancelyn Green dined with Lewis at Magdalen Higher. Afterward the meal, Lewis read two chapters from his new children'southward story to Dark-green. Lewis asked Dark-green's stance of the tale, and Green said that he thought information technology was good. The manuscript of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe was consummate by the end of March 1949. Lucy Barfield received it by the end of May.[xx] When on sixteen October 1950 Geoffrey Bles in London published the first edition, three new "chronicles", Prince Caspian, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, and The Horse and His Boy, had also been completed.

Illustrations [edit]

Lewis'due south publisher, Geoffrey Bles, allowed him to choose the illustrator for the novel and the Narnia series. Lewis chose Pauline Baynes, maybe based on J. R. R. Tolkien's recommendation. In December 1949, Bles showed Lewis the get-go drawings for the novel, and Lewis sent Baynes a note congratulating her, peculiarly on the level of detail. Lewis'southward appreciation of the illustrations is evident in a letter he wrote to Baynes later on The Final Battle won the Carnegie Medal for best children's book of 1956: "is information technology not rather 'our' medal? I'm sure the illustrations were taken into account, as well as the text".[21]

The British edition of the novel had 43 illustrations; American editions generally had fewer. The popular U.S. paperback edition published by Collier between 1970 and 1994, which sold many millions, had only 17 illustrations, many of them severely cropped from the originals, giving many readers in that country a very different feel when reading the novel. All the illustrations were restored for the 1994 worldwide HarperCollins edition, although these illustrations lacked the clarity of early on printings.[22]

Reception [edit]

Lewis very much enjoyed writing The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and embarked on the sequel Prince Caspian presently after finishing the first novel. He completed the sequel by cease of 1949, less than a yr after finishing the initial book. The King of beasts, the Witch and the Wardrobe had few readers during 1949 and was not published until tardily in 1950, and then his initial enthusiasm did non stem from favourable reception by the public.[23]

While Lewis is known today on the force of the Narnia stories equally a highly successful children'due south writer, the initial disquisitional response was muted. At the time, children's stories being realistic was fashionable; fantasy and fairy tales were seen equally indulgent, advisable simply for very immature readers and potentially harmful to older children, even hindering their ability to relate to everyday life. Some reviewers considered the tale overtly moralistic or the Christian elements overstated attempts to indoctrinate children. Others were concerned that the many trigger-happy incidents might frighten children.[24]

Lewis'due south publisher, Geoffrey Bles, feared that the Narnia tales would not sell, and might damage Lewis's reputation and affect sales of his other books. All the same, the novel and its successors were highly popular with young readers, and Lewis's publisher was shortly eager to release further Narnia stories.[25]

A 2004 U.Southward. study found that The King of beasts was a mutual read-aloud volume for seventh graders in schools in San Diego County, California.[26] In 2005, information technology was included on Fourth dimension 'southward unranked list of the 100 best English-language novels published since 1923.[27] Based on a 2007 online poll, the U.S. National Didactics Association listed it every bit one of its "Teachers' Acme 100 Books for Children".[28] In 2012, it was ranked number five among best children's novels in a survey published by School Library Journal, a monthly with primarily U.S. audition.[29]

A 2012 survey by the University of Worcester determined that information technology was the second-most common volume that Britain adults had read as children, later on Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. (Adults, perhaps limited to parents, ranked Alice and The Lion 5th and sixth as books the side by side generation should read, or their children should read during their lifetimes.)[30]

TIME included the novel in its "All-TIME 100 Novels" (all-time English-language novels from 1923 to 2005).[27] In 2003, the novel was listed at number 9 on the BBC's survey The Big Read.[31] It has also been published in 47 foreign languages.[32]

Reading guild [edit]

The matter of the reading club of the Narnia serial, in the context of the change in their publication club—from its original (outset with The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe) to the later adopted, now pervasive chronology-of-events lodge (kickoff with The Wizard'due south Nephew)—has been a matter of extensive discussion for many years.[33] The Lion... was originally published as the offset book in the Chronicles, and almost reprintings of the novels reflected that order, until difference with the Collins' "Fontana Lions" edition in 1980.[33] : 42 Change, however, had begun earlier—the listing of the books in the English language Puffins editions as early on equally 1974 presented a list every bit a suggested reading club that placed Magician's get-go—and with the Collins' edition, the motility to the chronological club, and the series opening with Magician's was formalised.[33] : 42 Walter Hooper, for i, was pleased with this, stating that the books could now be read in the club that Lewis' himself "said they should".[34] When HarperCollins presented its uniform, worldwide edition of the series in 1994, it as well used this sequence, going then far equally to country that its "editions of the Chronicles... accept been numbered in compliance with the original wishes of the writer, C.S. Lewis."[33] : 42–43

In a work of literary criticism, Imagination and the Arts in C. Southward. Lewis, scholar Peter J. Schakel calls into question the clarity and simplicity of these conclusions, citing a variety of evidences that oppose a atypical view of a correct viewing lodge, evidences that include Lewis' own words. Laurence Krieg, a young fan, wrote to Lewis, asking him to adjudicate betwixt his views of the correct sequence of reading the novels; he held to reading The Wizard's... first, while his mother thought The Panthera leo... should be read first. Lewis wrote back, stating support for the younger Krieg's views, just called rigid conclusions into question, stating: "I call up I agree with your society... [but] perhaps it does non thing very much in which order anyone reads them."[33] : 42–43

"I think I agree with your order for reading the books more than with your mother'southward. The series was not planned beforehand every bit she thinks. When I wrote The Lion, I did non know I was going to write whatever more. Then I wrote P. Caspian as a sequel and nevertheless didn't think there would be any more, and when I had done The Voyage, I felt quite sure it would be the last, but I institute I was incorrect. So perchance it does not affair very much in which order anyone reads them. I'g not even sure that all the others were written in the same order in which they were published."

—C. S. Lewis to Laurence Krieg, an American fan[35] [ page needed ]

Schakel'south writings go on to pointedly question the revised order in literary disquisitional analyses that recognise the view of Hooper, documents such as the Krieg letter, also as the commercial inclinations behind creation of later editions of works in a unique order, but nevertheless argue strenuously with regard to the change in the "imaginitive reading experience" in the afterward revised arrangement—the primal difference being that, in the original publication social club, the land of Narnia is carefully introduced in The Lion... (e.grand., the children hearing the term and having to take it explained), whereas in The Sorcerer'due south..., with its original publication second, has Narnia'south mention appearing on the first page, without explanation; a similar disconnection in experience is noted with regard to how the central character Aslan is experienced in the two reading orders.[33] : 46–48 Schakel argues the affair through repeated farther examples (east.g., the appearances of the lamppost, the depiction of the characters of the White Witch and Jadis, etc.), concluding that, "the 'new' organisation may well be less desirable that the original".[33] : 49, 44 Author Paul Ford likewise cites several scholars who have weighed in against the decision of HarperCollins to present the books in the order of their internal chronology,[36] and continues, "most scholars disagree with this decision and find it the least true-blue to Lewis's deepest intentions".[37]

Critically, the reissue of the Puffin serial in England, which was proceeding at the time of Lewis' death in 1963 (with 3 volumes out beginning with The Lion..., and the remaining four presently due) maintained the original order, with gimmicky comments ascribed to Lewis—made to Kaye Webb, the editor of that imprint—suggesting he yet intended "to re-edit the books... [to] connect the things that didn't tie upwardly".[33] : 44 [38] Regardless, as of January 2022, the publication society placing The Panthera leo, the Witch and the Wardrobe 2d in the series continues—in accord with Walter Hooper's perception of Lewis' intent, whether intended with or without further serial changes—such that it remains the production pattern for the series as it is distributed worldwide.[33] [39]

Allusions [edit]

Lewis wrote, "The Narnian books are non as much allegory as supposal. Suppose there were a Narnian world and it, like ours, needed redemption. What kind of incarnation and Passion might Christ be supposed to undergo there?"[40]

The main story is an allegory of Christ's crucifixion:[41] [42] Aslan sacrifices himself for Edmund, a traitor who may deserve death, in the aforementioned style that Christians believe Jesus sacrificed himself for sinners. Aslan is killed on the Stone Table, symbolising Mosaic Law, which breaks when he is resurrected, symbolising the replacement of the strict justice of Old Testament constabulary with redeeming grace and forgiveness granted on the basis of substitutionary amende, according to Christian theology.[43]

The graphic symbol of the Professor is based on W.T. Kirkpatrick, who tutored a 16-year-old Lewis. "Kirk", as he was sometimes called, taught the young Lewis much about thinking and communicating clearly, skills that would be invaluable to him subsequently.[44]

Narnia is caught in endless wintertime that has lasted a century when the children commencement enter. Norse tradition mythologises a "smashing winter", known equally the Fimbulwinter, said to precede Ragnarök. The trapping of Edmund by the White Witch is reminiscent of the seduction and imprisonment of Kai past the Snow Queen in Hans Christian Andersen'southward novella of that name.[45]

Several parallels are seen between the White Witch and the immortal white queen, Ayesha, of H. Rider Haggard's She, a novel greatly admired past Lewis.[46]

Edith Nesbit'due south brusque story "The Aunt and Amabel" includes the motif of a girl entering a wardrobe to proceeds access to a magical place.[47]

The freeing of Aslan's torso from the Stone Table is reminiscent of a scene from Edgar Allan Poe's story "The Pit and the Pendulum", in which a prisoner is freed when rats champ through his bonds.[48] In a later book, Prince Caspian, as reward for their deportment, mice gained the same intelligence and oral communication as other Narnian animals.[49]

Religious themes [edit]

One of the most pregnant themes seen in C. S. Lewis'south The Panthera leo, The Witch and The Wardrobe is the theme of Christianity.[50] Various aspects of characters and events in the novel reflect biblical ideas from Christianity. The lion Aslan is one of the clearest examples, every bit his expiry is very similar to that of Jesus Christ. While many readers made this connection, Lewis denied that the themes of Christianity were intentional, maxim that his writing began by picturing images of characters, and the residue just came about through the writing process.[51] While Lewis denied intentionally making the story a strictly Christian theological novel, he did admit that it could assistance immature children accept Christianity into their lives when they were older.[52]

After the children enter the world of Narnia through the wardrobe, Edmund finds himself in trouble under service of the White Witch, as she tempts him with Turkish delight. When Edmund is threatened with death, Aslan offers to sacrifice himself as an atonement for the boy'due south betrayal. Aslan is shaved of his fur, and stabbed on an chantry of stone. This is similar to how Jesus was publicly browbeaten, humiliated, and crucified. Later his sacrifice, Aslan is reborn, and he continues to assist the children save Narnia.[52] While this sequence of events is comparable to the death of Jesus, it is non identical to it. A few differences exist, such as the fact that Aslan did not permit himself to exist killed to save the entirety of Narnia, but just to save Edmund. Aslan is also simply dead for one night, while Jesus returned on the third day.[51] Despite these differences, the prototype of Aslan and the outcome of his death and rebirth reflect those of the biblical account of Jesus' death and resurrection, adding to the theme of Christianity throughout the novel.[51]

Differences betwixt editions [edit]

Due to labour-union rules,[53] the text of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe was reset for the publication of the first American edition by Macmillan The states in 1950.[1] Lewis took that opportunity to brand these changes to the original British edition published past Geoffrey Bles[3] earlier that same year:

- In chapter one of the American edition, the animals in which Edmund and Susan express interest are snakes and foxes rather than the foxes and rabbits of the British edition.[53] [54]

- In chapter six of the American edition, the name of the White Witch's chief of police is changed to "Fenris Ulf" from "Maugrim" in the British.[55] [56] [57]

- In chapter 13 of the American edition, "the trunk of the World Ash Tree" takes the identify of "the burn-stones of the Secret Loma".[58]

When HarperCollins took over publication of the series in 1994, they began using the original British edition for all subsequent English editions worldwide.[59] The current U.South. edition published past Scholastic has 36,135 words.[lx]

Adaptations [edit]

Tv set [edit]

The story has been adjusted three times for tv set. The first was a 10-part serial produced by ABC Weekend Television for ITV and broadcast in 1967.[ citation needed ] In 1979, an animated TV movie,[61] directed by Peanuts managing director Neb Melendez, was broadcast and won the showtime Emmy Accolade for Outstanding Animated Program.[ citation needed ] A third television adaptation was produced in 1988 past the BBC using a combination of alive actors, animatronic puppets, and animation. The 1988 adaptation was the first of a series of iv Narnia adaptations over iii seasons. The plan was nominated for an Emmy Accolade and won a BAFTA.[ commendation needed ]

Theatre [edit]

Stage adaptations include a 1984 version staged at London's Westminster Theatre, produced past Vanessa Ford Productions. The play, adapted past Glyn Robbins, was directed past Richard Williams and designed by Marty Flood.[62] Jules Tasca, Ted Drachman and Thomas Tierney collaborated on a musical accommodation published in 1986.[63]

In 1997, Trumpets Inc., a Filipino Christian theatre and musical production company, produced a musical rendition that Douglas Gresham, Lewis'southward stepson (and co-producer of the Walden Media picture show adaptations), has openly alleged that he feels is the closest to Lewis's intention.[64] [65] [66] Information technology starred among others popular young Filipino vocalizer Sam Concepcion as Edmund Pevensie.[67]

In 1998, the Royal Shakespeare Company did an accommodation by Adrian Mitchell, for which the acting edition has been published.[68] The Stratford Festival in Canada mounted a new production of Mitchell'due south work in June 2016.[69] [70]

In 2003, an Australian commercial stage production by Malcolm C. Cooke Productions toured the country, using both life-sized puppets and man actors. Information technology was directed by notable motion picture managing director Nadia Tass, and starred Amanda Muggleton, Dennis Olsen, Meaghan Davies, and Yolande Chocolate-brown.[71] [72]

In 2011, a two-histrion stage adaptation by Le Clanché du Rand opened off-Broadway in New York Urban center at St. Luke'south Theatre. The production was directed past Julia Beardsley O'Brien and starred Erin Layton and Andrew Fortman.[73] As of 2014, the production is currently running with a replacement cast of Abigail Taylor-Sansom and Rockford Sansom.[74]

In 2012, Michael Fentiman with Rupert Goold co-directed The Panthera leo, the Witch and the Wardrobe at a Threesixty 'tented production' in Kensington Gardens, London. It received a Guardian three-star review.[75]

Sound [edit]

Multiple audio editions have been released, both straightforward readings and dramatisations.

In 1981, Michael Hordern read abridged versions of the classic tale (and the others in the series). In 2000, an entire audio book was released, narrated by Michael York. (All the books were released in audio class, read past different actors.)

In 1988, BBC Radio 4 mounted a full dramatisation. In 1998, Focus on the Family Radio Theatre as well adapted this story. Both the original BBC version and the Focus on the Family unit version have been broadcast on BBC radio. Both are the first in a series of adaptations of all 7 of the Narnia books. The BBC serial uses the title Tales of Narnia, while the Focus on the Family unit version uses the more familiar Chronicles moniker. The Focus on the Family unit version is also longer, with a full orchestra score, narration, a larger cast of actors, and introductions by Douglas Gresham, C. S. Lewis's stepson.

Film [edit]

In 2005, the story was adapted for a theatrical film, co-produced by Walt Disney Pictures and Walden Media. It has so far been followed by ii more films: The Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian and The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. The latter was co-produced past 20th Century Fox and Walden Media.

References [edit]

Footnotes [edit]

- ^ a b c "The lion, the witch and the wardrobe; a story for children" (get-go edition). Library of Congress Catalog Record.

"The lion, the witch and the wardrobe; a story for children" (commencement U.South. edition). LCC record. Retrieved 2012-12-09. - ^ "Lewis, C. S. 1898-1963 (Clive Staples) [WorldCat Identities]". WorldCat . Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ^ a b "Bibliography: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe". ISFDB . Retrieved ix Dec 2012.

- ^ Schakel 2002 p. 75

- ^ "The Large Read - Top 100 Books". BBC. two September 2014. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ "100 All-time Young-Adult Books". Time . Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ "100 best English-linguistic communication novels published since 1923". Fourth dimension . Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ^ Letter to Anne Jenkins, 5 March 1961, in Hooper, Walter (2007). The Collected Letters of C. S. Lewis, Book III. HarperSanFrancisco. p. 1245. ISBN978-0-06-081922-4.

- ^ Lewis (1960). "It All Began with a Picture". Radio Times. 15 July 1960. In Hooper (1982), p. 53.

- ^ Ford, p. 106.

- ^ ""Of Other Worlds", past C. S. Lewis"" (PDF). Wayback Machine. 24 December 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on four September 2014. [ total citation needed ]

- ^ Edwards, Owen Dudley (2007). British Children's Fiction in the 2nd Globe State of war. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-7486-1650-3.

- ^ Green, Roger Lancelyn, and Walter Hooper (2002). C. S. Lewis: A Biography. Fully Revised and Expanded Edition. p. 303. ISBN 0-00-715714-2.

- ^ Lewis (2004 [1947]). Collected Letters: Book 2 (1931–1949). p. 802. ISBN 0-06-072764-0. Letter of the alphabet to East. L. Baxter dated ten September 1947.

- ^ Lewis (1946), "Different Tastes in Literature". In Hooper (1982), p. 121.

- ^ Walsh, Chad (1974). C. Southward. Lewis: Apostle to the Skeptics. Norwood Editions. p. ten. ISBN 0-88305-779-4.

- ^ Lewis (1960). In Hooper (1982), pp. xix, 53.

- ^ Lewis (1935), "The Alliterative Metre". In Hooper, ed. (1969), Selected Literary Essays, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521074414, p. 25.

- ^ Michael Ward (2008), Planet Narnia: the seven heavens in the imagination of C.Due south. Lewis, Oxford Academy Printing, ISBN 9780195313871.

- ^ Hooper, Walter. "Lucy Barfield (1935–2003)". Seven: An Anglo-American Literary Review. Volume xx, 2003, p. 5. ISSN 0271-3012. "The dedication ... was probably taken from Lewis'due south letter to Lucy of May 1949".

- ^ Schakel 2002, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Schakel 2002, p. 132.

- ^ Veith, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Veith, p. 12.

- ^ Veith, p. 13.

- ^ Fisher, Douglas, James Flood, Diane Lapp, and Nancy Frey (2004). "Interactive Read-Alouds: Is There a Common Set of Implementation Practices?" (PDF). The Reading Instructor. 58 (i): 8–17. doi:10.1598/RT.58.1.1. Archived from the original (PDF) on vii December 2013.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ a b Grossman, Lev (16 October 2005). "All-TIME 100 Novels: The Panthera leo, The Witch and the Wardrobe". Time. Archived from the original on 22 October 2005. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ National Education Clan (2007). "Teachers' Top 100 Books for Children". Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ Bird, Elizabeth (7 July 2012). "Top 100 Chapter Book Poll Results". A Fuse #viii Production. Blog. School Library Periodical (blog.schoollibraryjournal.com). Archived from the original on 13 July 2012. Retrieved 22 Baronial 2012.

- ^ "Top ten books parents recall children should read". The Telegraph. 19 August 2012. Retrieved 22 Baronial 2012.

- ^ "The Big Read - Height 100 Books". BBC. 2 September 2014. Retrieved nineteen October 2012.

- ^ GoodKnight, Glen H. "Translations of The Chronicles of Narnia past C.Due south. Lewis" Archived 3 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine (index). Narnia Editions & Translations (inklingsfocus.com). Updated 3 August 2010. Confirmed 2012-12-10.

- ^ a b c d e f yard h i Schakel, pp. xl-52 (Affiliate 3, entitled "It Does Non Matter Very Much"—or Does Information technology? The "Correct" Order for Reading the Chronicles)

- ^ Hooper, C.South. Lewis: A Companion and Guide, p. 453.

- ^ Dorsett, Lyle (1995). Mead, Marjorie Lamp (ed.). C. S. Lewis: Letters to Children. Touchstone. ISBN9780684823720. [ when? ] [ total citation needed ]

- ^ Ford, pp. xxiii–xxiv.

- ^ Ford, p. 24.

- ^ See footnote 5, citing Green and Hooper's C.Due south. Lewis: A Biography.

- ^ E.thousand., see HarperCollins Staff (Jan 2022). "The Chronicles of Narnia, seven Books in i Hardcover, Past C. S. Lewis, Illustrated by Pauline Baynes, On Sale: [beginning] October 26, 2004". HarperCollins.com . Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ James E. Higgins. "A Letter from C. S. Lewis". The Horn Book Magazine. October 1966. Archived 2012-05-24. Retrieved 2015-ten-17.

- ^ Lindskoog, Kathryn. Journey into Narnia. Pasadena, CA: Promise Publ Firm. ISBN 9780932727893. pp. 44–46.

- ^ Gormley, Beatrice. C. South. Lewis: The Man Behind Narnia. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802853011. p. 122. (2nd edition of C. S. Lewis: Christian and Storyteller. Eerdmans. 1997. ISBN 9780802851215.)

- ^ Lewis, C. Due south. (2007). The Nerveless Messages of C.S. Lewis, Volume three: Narnia, Cambridge, and Joy, 1950 - 1963. Zondervan. p. 497. ISBN978-0060819224.

- ^ Lindsley, Fine art. "C. S. Lewis: His Life and Works". C. S. Lewis Institute. Retrieved 10 Nov 2016.

- ^ "No sex in Narnia? How Hans Christian Andersen's "Snow Queen" problematizes C. S. Lewis'southward The Chronicles of Narnia". Free Online Library (thefreelibrary.com). Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- ^ Wilson, Tracy Five (vii Dec 2005). "Howstuffworks "The World of Narnia"". Howstuffworks.com. Retrieved 21 Dec 2010.

- ^ Nicholson, Mervyn (1991). "What C. S. Lewis Took From E. Nesbit". Children's Literature Association Quarterly. 16: sixteen–22. doi:10.1353/chq.0.0823. Retrieved 1 Dec 2014.

- ^ Aesop's Fables by Aesop. Projection Gutenberg. 25 June 2008. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ Prince Caspian, Chapter fifteen.

- ^ Jackson, Ruth (26 April 2021). "The CS Lewis podcast" (Podcast). Premier Christian Radio. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ a b c Schakel, Peter J. (2013). "Hidden Images of Christ in the Fiction of C. S. Lewis". Studies in the Literary Imagination. Projection Muse. 46 (2): 1–18. doi:10.1353/sli.2013.0010. ISSN 2165-2678. S2CID 159684550.

- ^ a b Russell, James (27 September 2009). "Narnia as a Site of National Struggle: Marketing, Christianity, and National Purpose in The Chronicles of Narnia: The Panthera leo, the Witch and the Wardrobe". Cinema Journal. 48 (four): 59–76. doi:10.1353/cj.0.0145. ISSN 1527-2087.

- ^ a b Brown, Devin (2013). Within Narnia: A Guide to Exploring The King of beasts, the Witch and the Wardrobe. Abingdon Printing. ISBN978-0801065996.

- ^ Schakel, Peter (2005). The Fashion into Narnia: A Reader's Guide. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN978-0802829849. p. 122.

- ^ Bong, James; Dunlop, Cheryl (2007). The Complete Idiot'south Guide to the World of Narnia. Alpha. ISBN978-1592576173.

- ^ Hardy, Elizabeth (2013). Milton, Spenser and The Chronicles of Narnia: Literary Sources for the C.South. Abingdon Press. ISBN9781426785559. pp. 138, 173.

- ^ Ford, p. 213.

- ^ Ford, p. 459.

- ^ Ford, p. 33.

- ^ "Scholastic Catalog - Book Data". src.scholastic.com . Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe at IMDb

- ^ Hooper, Walter (1998). C. S. Lewis: A Complete Guide to His Life & Works. HarperCollins. pp. 787, 960.

- ^ WorldCat libraries have catalogued the related works in different ways including "The king of beasts, the witch, and the wardrobe: a musical based on C.Southward. Lewis' classic story" (book, 1986, OCLC 14694962); "The lion, the witch, and the wardrobe: a musical based on C.S. Lewis' archetype story" (musical score, 1986, OCLC 16713815); "Narnia: a dramatic adaptation of C.Due south. Lewis'southward The king of beasts, the witch, and the wardrobe" (video, 1986, OCLC 32772305); "Narnia: based on C.Southward. Lewis' [classic story] The panthera leo, the witch, and the wardrobe" (1987, OCLC 792898134).

Google Books uses the title "Narnia – Full Musical" and hosts selections, peradventure from the play by Tasca solitary, without lyrics or music. Tasca, J. (1986). Narnia - Full Musical. Dramatic Publishing Company. ISBN978-0-87129-381-vii . Retrieved sixteen June 2014. - ^ "Trumpets The Lion The Witch and the Wardrobe". TheBachelorGirl.com. 29 December 2005. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2010. Evidently, "the Bachelor Girl" was a former fellow member of the Trumpets cast.

- ^ David, B.J. [2002]. "Narnia Revisited". From a Filipino school newspaper, probably in translation, posted 12 September 2002 to a give-and-take forum at Pinoy Exchange (pinoyexchange.com/forums). Retrieved 2015-ten-29.

"Stephen Gresham, stepson of C.Southward. Lewis" saw the 2nd staging by invitation and returned with his wife to see it again. "[T]his approving from the family unit and estate of the well-loved author is enough testify that the Trumpets adaptations is at par with other versions." - ^ Run into also web log reprint of local paper article at David, BJ (24 May 2021). "The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe - Meralco, 2002 - Page half dozen - Books and Literature". PinoyExchange . Retrieved xix June 2021. . Article in English language. Blog in Filipino.

- ^ Garcia, Rose (29 March 2007). "Is Sam Concepcion the next Christian Bautista?". PEP (Philippine Entertainment Portal). Retrieved 11 Dec 2010.

- ^ Mitchell, Adrian (four December 1998). The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe: The Royal Shakespeare Company's Stage Accommodation. An Interim Edition. Oberon Books Ltd. ISBN978-1840020496.

- ^ "Stratford Festival puts magic of Narnia onstage: review". thestar.com. 3 June 2016.

- ^ "Stratford Festival'southward The Panthera leo, the Witch and the Wardrobe not for grown-ups" – via The Globe and Mail.

- ^ Murphy, Jim (2 January 2003). "Mythical, magical puppetry". The Age (theage.com.au) . Retrieved eleven December 2012.

- ^ Yench, Belinda. "Welcome to the lion's den". The Blurb [Australian arts and entertainment] (theblurb.com.au). Archived from the original on 8 September 2007. Retrieved 11 Dec 2010. . This review mistakenly identifies C. S. Lewis equally the author of Alice in Wonderland.

- ^ Quittner, Charles. "The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe Is Cute and Compact". BroadwayWorld.com . Retrieved 20 September 2014. [ expressionless link ]

- ^ Graeber, Laurel (4 September 2014). "Spare Times for Children for 5-11 Sept". The New York Times . Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ Billington, Michael (31 May 2012). "The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe – review". the Guardian . Retrieved nine December 2018.

Bibliography [edit]

- Ford, Paul F. (2005). Companion to Narnia: Revised Edition. San Francisco: HarperCollins. ISBN978-0-06-079127-8.

- Hooper, Walter, ed. (1982). On Stories and Other Essays on Literature. By C. Due south. Lewis. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 0-15-668788-7.

- Schakel, Peter J. (2002). Imagination and the arts in C. S. Lewis: journeying to Narnia and other worlds. University of Missouri Press. ISBN978-0-8262-1407-two.

- Veith, Gene (2008). The Soul of Prince Caspian: Exploring Spiritual Truth in the Country of Narnia. David C. Melt. ISBN978-0-7814-4528-3.

Further reading [edit]

- Sammons, Martha C. (1979). A Guide Through Narnia. Wheaton, Illinois: Harold Shaw Publishers. ISBN978-0-87788-325-eight.

- Downing, David C. (2005). Into the Wardrobe: C. S. Lewis and the Narnia Chronicles. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. ISBN978-0-7879-7890-seven.

- Ryken, Leland; Mead, and; Lamp, Marjorie (2005). A Reader's Guide Through the Wardrobe: Exploring C. S. Lewis's Classic Story. London: InterVarsity Press. ISBN978-0-8308-3289-7.

External links [edit]

- The Panthera leo, the Witch and the Wardrobe at Faded Page (Canada)

- The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe in libraries (WorldCat itemize) —immediately, the full-color C. S. Lewis centenary edition

- The Panthera leo, the Witch and the Wardrobe title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Lion,_the_Witch_and_the_Wardrobe

Post a Comment for "Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe Original Edition Art"